Aspirations to be “greener” and a need to cut costs in an unstable economy have obliged galleries and museums to trim or eliminate their printing budgets. Whereas mailed postcards and press releases once accompanied exhibitions, today’s publicity often comes only electronically. While many would shrug their shoulders at another twentieth-century practice rendered obsolete, those who prize physical documents recognize that while websites disappear and tweets get buried, paper can last for years, serving as crucial primary art-historical documentation.

The artist Lawrence Weiner obliquely references ephemera’s slow disappearance in AN ABROGATION OF THE INHERENT DESTINY OF ANY OBJECT AT HAND (2011), a work consisting of those words spelled out on black and silver vinyl that spans ten feet on a wall inside Susan Inglett Galley. It’s his singular official contribution to the exhibition Specific Object Presents Lawrence Weiner’s Published Work from the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project. The approximately 450 other pieces are culled from the collection of Herlin, a Frenchman who ran an antiquarian bookstore in Soho from 1972 to 1987 and had the foresight to save art-related paperwork.

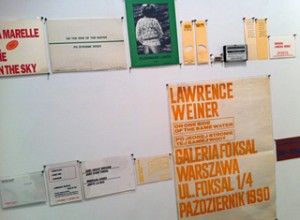

Organized by David Platzker of Specific Object, which specializes in books and printed matter, the exhibition focuses exclusively on Weiner, whose use of language as sculptural material has long contested the traditional form and display of art. Housed in custom-fitted plastic sleeves and arranged chronologically in three parallel rows on each gallery wall are announcement cards, press releases, posters, flyers, event programs, book and magazine covers, clippings of newspaper reviews, photographs, audiocassette j-cards, and much more. Slivers of manila file folders from the archive, with Herlin’s handwritten notation, give rhythm to the sequential arrangement. Pairing this particular artist with these kinds of “published works” brilliantly calls into question conventional ideas about the role of archives, exhibitions, research, collecting, and above all value.

Weiner has repeatedly stated that it does not matter if his work is built (it can remain a text) or if he builds it himself. The exhibition’s starting point, Turf, Stake and String (1968), is a sticker based on a drawing for a sculpture at Windham College in Vermont, the destruction of which led the artist to this casual approach. Thus a work like THE SALT OF THE EARTH MINGLED WITH THE SALT OF THE SEA (ca. 1984) is identical whether printed on a museum wall or typeset on cardstock—or if the action is accomplished physically. Likewise a text piece placed among advertisements in a German train schedule is art, but an invitation letter from Who’s Who in America or a mailing label ripped from a package has a harder case to make. While early printed materials may be valued for their rarity, their presentation varied. Weiner’s now-recognizable style of font, color, and design seems to have developed in the early 1980s.

Artifact or memorabilia, Published Work gives equal billing to both categories, enhancing the work of scholars who might make insightful observations about the artist’s development. Yet many items on view are double-sided, so the exhibition only tells half the story—indicative of the archive’s role as partial source for historical reconstruction. Most of all, Published Work demonstrates how Weiner, usually labeled a Conceptual artist, strove not to dematerialize art but to make it diffuse and available to everyone.

Originally published as “A Weiner Hoarder Shows His Cards” in the L Magazine on July 6, 2011.