Olga M. Viso

Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance, 1972–1985

Washington, DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, in association with Hatje Cantz, 2004

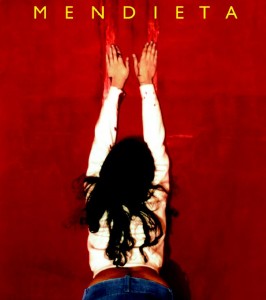

Ana Mendieta’s “earth-body works,” a unique combination of conceptual, earth, and body art continues to captivate audiences and fascinate scholars. Mendieta, an American artist born in Cuba, created a remarkable body of work—ephemeral outdoor performances and creations documented in photographs, 35mm slides, and Super-8 films, as well as sculpture and drawing—before her life tragically ended in 1985 at age thirty-six. Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance, 1972–1985 is a catalogue for the traveling exhibition of the same name, on view in the United States through 2006. This book is the most thoroughly researched, well-illustrated, and balanced account to date of this singular, extraordinary artist, and through the work of the exhibition curator and primary author Olga Viso, Mendieta conclusively takes her rightful place as one of the most important and influential artists of the late twentieth century.

In her introduction, Viso considers previous interpretations of Mendieta’s art: the artist’s interest in the art of pre-Columbian cultures; issues of female identity, voice, and authority; expressions of loss, absence, and displacement; and her relationship to and reinvention of conceptually based process and performance practices. Viso describes her purpose: “By correcting a number of biographical inaccuracies and challenging long-held assumptions about Mendieta’s evolution as an artist and the critical contexts in which her art has been framed, we are able to examine comprehensively her significant contributions to the art of our time.” This project is important, Viso claims, because until the mid-1990s Mendieta’s work was rarely shown outside a feminist or Latino/a context—a problem that beleaguered the artist even during her own lifetime.

Thus, for this exhibition and the catalogue main essay, “The Memory of History,” Viso researched the biographical, creative, and professional elements of Mendieta’s life, seamlessly weaving family history, personal details, artistic achievements, and critical analyses. Following Mendieta’s footsteps, she traveled to Cuba, Italy, and Mexico (the latter country with Hans Breder, the artist’s teacher, mentor, and lover during the 1970s), as well as across the USA, to gather her material. Incredibly well researched—344 endnotes identify a vast well of sources, from the artist’s personal archives and interviews with family members to newspaper accounts and critical essays—the book is traditional art history at its finest.

Written for the specialist and a general audience, Viso’s text is the most readable of any account of Mendieta’s art and life. The author sets the stage by giving a general overview of midcentury avant-garde practices and movements and by providing a general overview of the early days of the University of Iowa’s Intermedia Program. There we find the source of Mendieta’s working practice: Viso writes, “Breder’s teaching emphasized the following process, to which Mendieta subscribed throughout her career: 1) formulate a proposal for the work; 2) execute it; 3) document the activity.” Viso also credits other key influences on the artist: literary and artistic sources, her visits to Mexico from 1971 to 1977, and her friendship with the critic and art historian Lucy Lippard, who was the first to write about the artist.

Viso then traces chronologically both Mendieta’s biography and her body of work, from her early student performances to her sculpture, drawing, and the outdoor projects created in the last few years of her life. The author’s interpretations are subtle yet complex; they may disappoint those readers interested in postcolonial, feminist, and critical theory, as the author favors a close examination of the works, their background and context, and their multiplicity of meaning over themes of identity and sexual politics (though Viso does not avoid them). Readers will still want to consult Gloria Moure’s 1996 monograph on Mendieta, especially Charles Merewether’s insightful essay [in it], and Jane Blocker’s theoretically charged Where Is Ana Mendieta? to find out what Viso gracefully sidesteps.

The outline of the female form in nature that stresses a feminist sensibility, if not feminist politics, is clear in Mendieta’s work. To this end, Viso examines the artist’s relationship to the leading women artists of the day, including Mary Beth Edelson, Carolee Schneemann, and Nancy Spero. Viso connects Mendieta more closely with European-based artists such as Marina Abramovic, Hannah Wilke, Teresa Hak Kyung Cha, and Rebecca Horn, whose work is perhaps more poetic and less didactic than that of their American counterparts (but no less imperative and poignant). I would add to this list Valie Export, whose urban Body Configurations photographs of the mid-1970s uncannily parallel Mendieta’s contemporaneous work in nature.

In the 1980s, Mendieta’s creative processes moved from photodocumentation of ephemeral events “to make works that were more readily marketable, which aided her quest for gallery representation.” This understudied work—freestanding sculpture, floor pieces, wall reliefs, and drawings—is ripe for reevaluation, and Viso’s research will surely help to launch further studies. Concluding her essay, the author touches on Mendieta’s personal and professional relationship with the sculptor Carl Andre, whom she met in 1979 and married in 1985, but generally avoids speculating on the circumstances surrounding her death. Not to leave us with a grim ending, Viso traces the influence of Mendieta on artists working today.

Mendieta is one of the few contemporary artists who has achieved acclaim for student work. Julia Herzberg’s essay, “Ana Mendieta’s Iowa Years, 1970–1980,” chronicles the artist’s growth from young graduate student to sophisticated artist. Mendieta attended the University of Iowa, one of the most progressive art schools in the 1960s and 1970s, from 1966 to 1977, earning a bachelor’s and two master’s degrees (the work for which she is known today comes from 1972 and after). Breder was certainly a crucial force for many Intermedia students during this time: he brought in several visiting professors—Scott Burton, Vito Acconci, Robert Wilson, and Willoughby Sharp among them—who provided direct access to major art-world figures and trends. Herzberg also identifies Mendieta’s first summer trip to Mexico in 1971 with an archaeology class as an experience that opened her fully to pre-Columbian art, which she came to believe was superior to Western art. Like Viso, Herzberg performs excellent close readings of Mendieta’s student work, including her provocative “blood pieces” and “tableaux of violence” works. By 1977, the artist had already completed a formidable body of work: her best-known works, the Silueta, Fetish, and Tree of Life series, establish her today as a leading practitioner of emotionally and physically charged process and performance art.

Guy Brett’s essay places Mendieta’s work in the context of her Latin American peers—an interesting perspective that, the author admits, deserves additional study. He writes, “Mine is not an attempt to trace influences, but rather affinities, parallels, simultaneities, resonances, ideas ‘in the air’ at given moment….” Brett explores two themes in Mendieta’s work, fire and earth, and connects them to a certain Latin American sensibility that is also found in the work of Hélio Oiticica, Marta Minujín, Cildo Meireles, and Grupos Escombros. These artists use fire and earth, however, to engage social and political issues more directly than Mendieta, who strove for the personal and timeless. His third theme, “Self, Selves,” which contrasts Mendieta’s solitary figures with Lygia Clark’s social performances, fails to convince as a specifically Latin American construct. Each artist’s work is open ended and emphasizes an exhaustion of the self, but by the mid-twentieth century artists around the world were exploring concepts of the self and the body.

In “Subtle Bodies: The Invisible Films of Ana Mendieta,” Chrissie Iles duly notes that Mendieta created the largest number of artist’s films in the 1970s—eighty in all—but has only recently received proper recognition: in fact, with this very exhibition. Iles points out that Mendieta used three-minute Super-8 film cartridges, a medium that in the 1970s many artists cast aside in favor of newer video technology. As most video equipment was rare outside the television studio, Super-8 was still the medium of choice—as was 35mm slide film—for families, amateurs, and populist-minded artists. Interestingly, Iles mentions that Mendieta’s films lack a sound track, acting as “silent witness[es] to her ephemeral sculptural works and actions in the gallery, on the street, and, most extensively, in the land….” In contrast, she also notices “strong feminist overtones” in films such as Untitled (Body Tracks) that demonstrate a visceral side to the films’ contemplative and occasionally lyrical atmosphere.

At the end of the book appears a chronology, compiled by Laura Roulet, which alternates between the artist’s biography, family history, and artistic milestones and general social, political, and art history. An extensive bibliography, a detailed exhibition history, and a complete checklist of the exhibition are also included (the latter essential, as the illustrations appear throughout the volume in random order).

An exceptional monograph, Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance, 1972–1985 will be the first resource interested readers will consult; however, since biography plays a central role in the book, previous scholarship, including Moure’s catalogue and Blocker’s study, should also be consulted for their theoretical approaches. Nonetheless, Viso and her contributors have provided a thorough history of Mendieta with splendid reproductions from every part of her career.

Originally published in the Art Book in May 2005.